What Is an Inciting Incident in a Story? It’s Not a Spark. It’s a Hinge.

Most writing guides teach that the inciting incident starts the story. But that model confuses chronology with causality. The inciting incident isn’t a spark: it’s a hinge. It’s the final beat that locks the narrative into motion, the first moment after which everything must happen.

What Is a Scene? The Most Common Misconception in Fiction Writing

Most writers think of a scene as the place where stuff happens. But a real scene is a unit of structural change: a high-stakes character pursues a goal, meets real resistance, and hits an escalation that shifts the story. If it doesn’t turn, it doesn’t count.

Dialogue As Action

Most writers think dialogue is how characters convey information. It's not. It's how they try to win.

What Is a Premise in a Story? Why It Matters and How to Write One That Generates Plot

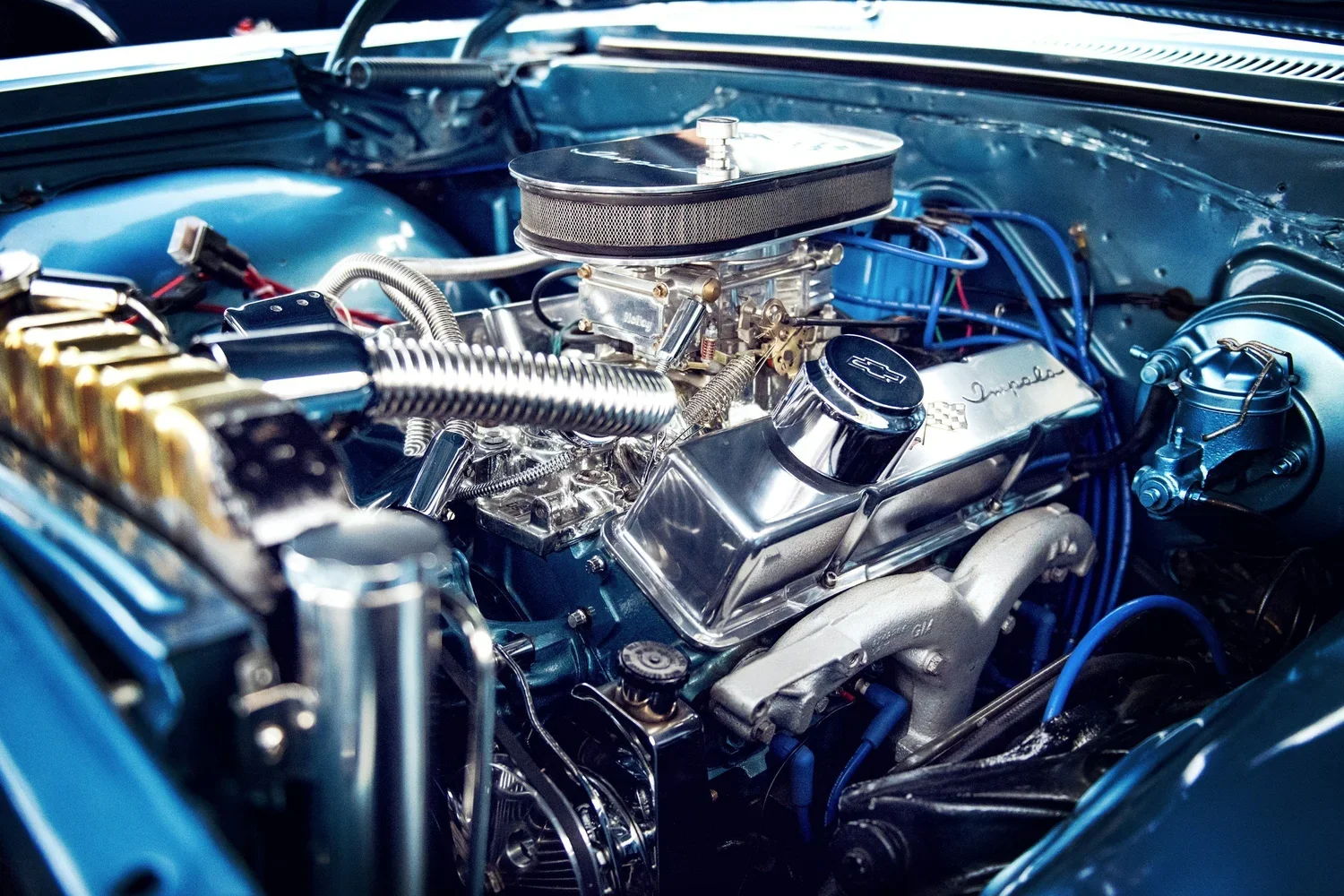

A premise is the engine of a story. It’s not a summary, a theme, or a description of subject matter. A premise defines the central struggle of a narrative in a way that automatically generates plot.

How to Write Setting That Drives Story: Setting Isn’t Backdrop. It’s the Engine

Most writers treat setting like wallpaper. But setting isn’t just what surrounds the story, it’s what acts on it. It’s the fusion of physical detail, body-in-space, and POV voice that generates narrative pressure and emotional atmosphere. This guide breaks down how to use setting as a structural force, not decorative backdrop, so every scene gains momentum, tension, and meaning.

Scenes Aren’t Enough: How to Build Sequences That Matter

Most writers know how to write scenes. Fewer know how to link them. Fewer still design sequences that escalate tension, deepen character change, and carry real momentum between acts. The result is fiction that moves but doesn’t evolve. This essay breaks down the five design pillars of effective sequences and shows how to avoid the most common mistake: not designing them at all.

No, an Outline Is Not a Scene List

Most outlines fail because they track time,not tension. If you're stuck in "and then" plotting, you need a new unit of design: the sequence.

Not All Opposites Are Foil Characters. Not All Doubles Are Mirror Characters.

If your cast “contrasts” the protagonist but doesn’t change the story, you don’t have a foil or mirror. You have noise. This essay shows you how to fix it.

Cause and Effect: How to Make Time Move on the Page

Most writing guides teach plot or prose—but few teach how time moves. This guide reveals the hidden structure behind real-time storytelling: the neurological chain of cause and effect. Learn to anchor beats in pressure, preserve micro-tension, and write scenes that feel lived, not just read. Once you understand how time flows through the line, your fiction stops floating and starts gripping.

How to Use Narrative Tableaux in Fiction

Not every moment has to move. Narrative tableaux are static, emotionally charged beats that don’t progress the plot but deepen everything around it. This essay shows how to use them without stalling the story.

Designing Flashbacks In Fiction

A flashback isn’t a memory dump. It’s a pressure device. It must interrupt the present, reframe the stakes, and end in a turn. This essay shows how to structure flashbacks that change the story not just explain it.

You Don’t Hate Writing. You Hate That It’s Not Getting Better

Praxis is a free craft trainer for fiction. It does not write for you. It installs goal, obstacle, escalation, and turn so every scene ends in a real change. Built from the Not MFA system I’ve used with writers for seven years.

The Rule of 3

The triangle is the most stable structure in the world. Bridges endure because trusses share load. Roofs keep their pitch in weather because rafters brace in threes. Sailors find speed by tacking between shifting winds and a fixed keel. Musicians stack triads so tension can hold and then resolve. Strength and motion at once. That is the geometry you need on the page.

Subtext You Can Build

Subtext is design, not mood. Build it in six moves: set aims, cut the honest line, name the cost, choose a behavioral leak, raise the risk once, and time escalation to a line or a gesture. Use dramatized dialogue, spare monologue, and narratized bridges to keep pressure on the page.

What Shirley Jackson Designed: System Antagonist in The Lottery

Read The Lottery like a writer and watch ritual and communal complicity turn a town into the antagonist and shape a catharsis you feel in your bones.

Embrace Your Villain Nature: Why Every Story Starts with the Antagonist

Forget what you’ve been told: don’t start with your protagonist. Embrace your villain nature. Start with their opposition. Start with pressure. Start with the thing that makes story happen.

What Hemingway Designed: Character in Hills Like White Elephants

Characters aren’t who they say they are—they’re what they do. In Hills Like White Elephants, Hemingway builds two people whose wants and needs grind together until one breaks and the other is revealed. This is how to design a character arc that ends in rupture, exposure, or both.

Character Is Conflict

There are no plot-driven stories. There are no character-driven stories. There are only character-driven plots. Every decision your protagonist makes leaves a trail—that trail is your plot. This essay breaks down how to build characters whose internal needs and external goals collide, generating narrative momentum and emotional depth that readers won’t forget.

What Hemingway Designed: Dialogue in “Hills Like White Elephants”

Dialogue in this story is a pressure system: characters want things, and they want them from each other. Every line spoken is an attempt. Every response is either resistance or retreat. There’s no idle talk. Just two people trying to win a scene neither can.

Dialogue Isn’t What They Say—It’s What They Do

Torque is the difference between plot and story. Most writers escalate conflict. But torque bends character. This essay breaks down how it works—and how to structure it.